Gruline on the Isle of Mull is home to a modest stone structure with international historical significance. This is the mausoleum of Lachlan Macquarie, Governor of New South Wales from 1810 to 1821. Often referred to, though not without controversy, as the Father of Australia. For most passersby, it is a quiet enclosure of gable-ended stonework and weathered memorial panels. But beneath its modest appearance lies the final chapter of a man who helped shape a continent, and whose legacy remains debated two centuries later.

Major General Lachlan Macquarie, 5th Governor of New South Wales, 1 January 1810 – 30 November 1821.

The man from Ulva

Lachlan Macquarie was born on the Isle of Ulva, just off the west coast of Mull, in 1761. His family belonged to the Clan MacQuarrie, part of the Gaelic nobility that once held influence in the Hebrides. Despite noble ancestry, the family’s fortunes had declined, so Macquarie pursued a military career. He joined the British Army in 1775 at the age of 14.

He served in North America during the American War of Independence, later in India with the 77th Regiment of Foot, and also in Egypt during the campaign against Napoleon’s forces. It was likely during this period that he contracted venereal disease, believed to be syphilis, which lingered and contributed to his later health issues.

Despite the physical toll of military service, Macquarie rose through the ranks. He was known for his discipline and administrative skills, and in 1809 he was appointed Governor of New South Wales.

He arrived in Sydney on the first day of 1810, prepared to restore order and implement reform in a young colony still recovering from the Rum Rebellion.

Reform and controversy

Macquarie’s tenure as Governor saw widespread changes across New South Wales. His leadership helped transition the settlement from penal colony to a structured society. His most notable contributions included the introduction of a regulated currency, construction of roads and public buildings, and the development of markets and sanitation infrastructure.

He also promoted the rights and opportunities of emancipated convicts, allowing many to own land and work in public service. This policy was unpopular among Sydney’s elite, and it drew criticism from officials in London.

Macquarie’s legacy is complex. He encouraged social development and promoted equality among settlers, but his approach toward Indigenous Australians was harsh. In 1816, he authorised a military expedition that led to the Appin Massacre, where troops killed several Aboriginal people in retaliation for conflicts with settlers. He justified this in official correspondence, stating it was necessary to maintain order.

Today, opinions vary. Some view him as a progressive builder of civil society, others as a man whose reforms were built on the violence of colonial expansion.

Ship Hugh Crawford that brought immigrants to Australia in the 1820s. George L. Tuthill, 1824

Final years and death

By 1820, Macquarie’s health had deteriorated. Years of campaigning, tropical conditions, and long sea voyages had taken their toll. He requested to resign and returned to Britain in 1822 aboard the Hugh Crawford, accompanied by his wife Elizabeth and their son Lachlan Junior.

Macquarie made a final trip to the Isle of Mull, where he selected a burial spot at Gruline. He died in London on 1 July 1824 at the age of 62. He suffered from bladder and kidney disease, with symptoms that matched what was then called dropsy, a condition involving fluid retention. His earlier syphilitic infection likely worsened his decline.

His funeral took place with military honours, and his remains were returned to Mull in accordance with his wishes.

MacQuarie’s Mausoleum

The mausoleum and memorial

The structure was built around 1851, commissioned by Elizabeth Campbell Macquarie, with assistance from the Drummond family who then owned the Gruline estate. It is a simple rectangular building, constructed from ashlar sandstone, with a pitched roof made from stone slabs. At the corners and gable ends are engaged buttresses, and each gable is topped with a stone finial.

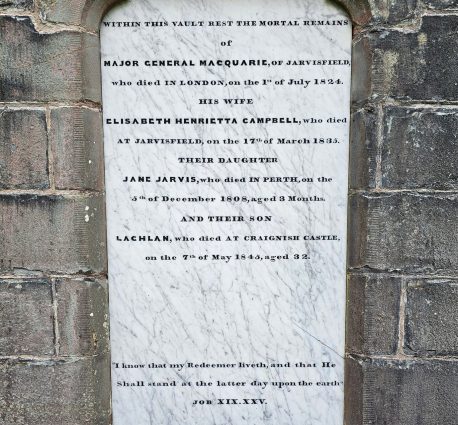

The original doorways were sealed with two memorial panels. One, made from red Peterhead granite, commemorates Lachlan Macquarie. The other, carved in white Carrara marble, honours Elizabeth and their children. Although Elizabeth is buried in London, she chose to install her memorial at Gruline beside her husband’s.

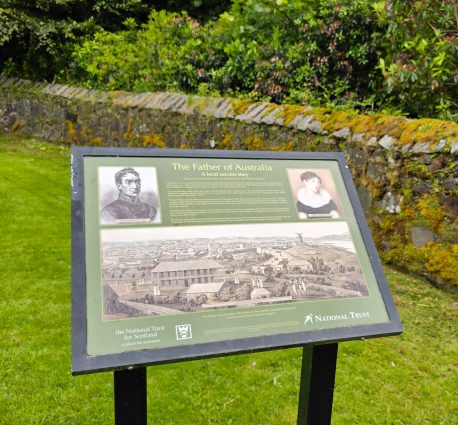

The mausoleum stands within a circular walled enclosure. Restoration work in the 1960s added wrought iron gates and stabilised the stonework. It has since been jointly maintained by the National Trusts of Scotland and New South Wales.

Visiting information

MacQuarie’s Mausoleum is located near the B8035, about three miles southwest of Salen. Visitors may park at the roadside lay-by and walk roughly 500 metres along a gravel path. The track passes through three gates and runs beside private homes. There are no signs, toilets, or visitor facilities on site.

Dogs should be kept on leads, and all gates should be left as found. The walk is level and manageable, though it can be muddy after rain. Visitors are asked to respect the privacy of residents.

Most people spend 10 to 15 minutes at the mausoleum.

Preservation and significance

In 1948, the mausoleum and its grounds were gifted by Lady Yarborough to the people of New South Wales. A trust was formed and later absorbed by the National Trust of Australia. Since 1971, it has been jointly managed with the National Trust for Scotland. Restoration and inspection efforts have kept the site intact and accessible.

Though small in size, the monument at Gruline links a Scottish settlement to the early colonial history of Australia. It marks the resting place of a man whose actions shaped the course of settlement, governance, and expansion. His legacy remains debated, but the site offers a point of reflection for those willing to seek it.

Whether you arrive knowing the name or simply curious about the stone structure behind the wall, MacQuarie’s Mausoleum offers quiet insight into the life of a figure whose influence travelled far beyond Mull.