In the centre of the village on the Isle of Iona stand the quiet stone ruins of Iona Nunnery. While many visitors focus their attention on the nearby Abbey, the nunnery tells an equally important story about religious life on the island. These remains mark the site of a medieval convent where women lived, prayed, and worked as part of Iona’s long Christian tradition.

Iona has held religious importance for more than a thousand years. Since the arrival of St Columba in the 6th century, the island has drawn monks, scholars, and pilgrims from across Britain and beyond. Over time, religious life on Iona expanded beyond the Abbey, and by the medieval period, a community of nuns also formed part of the island’s spiritual landscape.

What Is Iona Nunnery

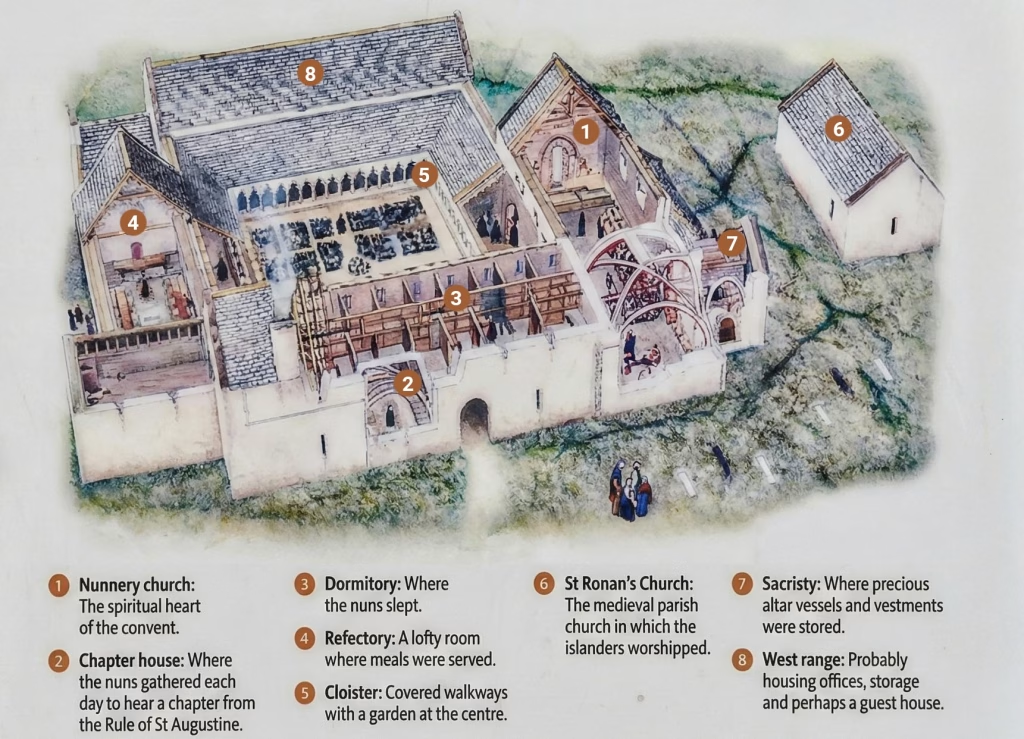

Iona Nunnery is the remains of a medieval convent built for Augustinian nuns. Today it survives as a group of roofless stone buildings arranged around what was once a central cloister. Although time and weather have taken their toll, the layout of the site remains clear and allows visitors to understand how the convent once functioned.

The nunnery stands close to the main village street, yet its enclosed layout creates a quieter and more sheltered space. Unlike the Abbey, which dominates the landscape with its scale, the nunnery feels modest and practical. This reflects its purpose as a place of daily religious life rather than a grand ceremonial centre.

The site includes the remains of the convent church, living quarters, and communal spaces. Together, these buildings supported a small but active religious community for several centuries.

Foundation and Early History

The nunnery was founded in the early 13th century during a period of renewed religious activity on Iona. Raghnall mac Somairle*, son of Somerled and Lord of the Isles, established the convent as part of wider efforts to strengthen religious institutions on the island. His family played a significant role in supporting church foundations across the western seaboard of Scotland.

Raghnall appointed his sister, Bethóc, as the first prioress of the nunnery. Her position gave the new convent both leadership and protection at an important stage in its development. The nunnery followed the Augustinian rule, making it one of a small number of Augustinian convents for women in medieval Scotland.

The foundation of the nunnery took place alongside rebuilding work at Iona Abbey. Together, these developments marked a revival of religious life on the island after earlier periods of disruption.

Life Within the Convent

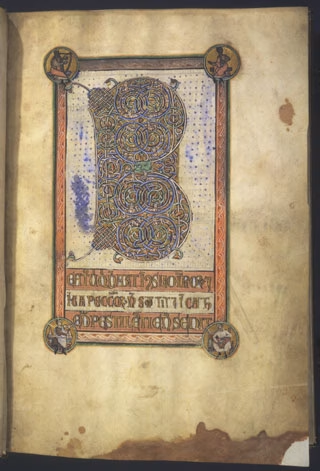

Few detailed records survive about the individual women who lived at Iona Nunnery. However, as members of an Augustinian convent, the nuns would have followed a structured religious routine shaped by prayer, communal worship, and daily responsibilities.

The nuns gathered regularly in the convent church and lived together as a community. Alongside religious duties, they managed practical tasks needed to support the convent, including caring for buildings and overseeing land or income linked to the house. Their lives combined spiritual focus with everyday work.

Although the nuns lived separately from the monks of the Abbey, the two communities remained connected through shared religious traditions and the wider life of the island. The nunnery formed an important part of Iona’s medieval society rather than existing in isolation.

Architecture and Layout

The layout of Iona Nunnery follows a traditional medieval convent plan. At its centre lay a square cloister, which acted as the heart of daily life. Covered walkways once surrounded this space and linked the main buildings of the convent.

The convent church stood on one side of the cloister, while other buildings included living quarters, a chapter house, and a refectory where the nuns shared meals. Even in ruin, the outlines of these spaces remain visible and help visitors picture how the convent once operated.

The stonework shows careful but restrained craftsmanship. Builders focused on strength and function rather than decoration, reflecting the practical needs and spiritual discipline of convent life.

Later History and Decline

The nunnery continued in use until the Scottish Reformation in the mid 16th century. During this period, religious houses across Scotland faced closure, and monastic life on Iona came to an end.

After the nuns left, the buildings fell into disrepair. Roofs collapsed, walls weathered, and the convent gradually became a ruin. Some local traditions hold that nuns from Iona may have sought refuge in the Nun’s Cave at Carsaig on Mull during the upheaval of the Reformation, which is how the cave got its name, though there is no direct historical evidence to confirm this. Unlike Iona Abbey, the nunnery did not undergo full restoration in later centuries.

This lack of rebuilding has preserved the site’s open and ruinous character. Today, the remains offer a direct and unaltered view of the medieval structure.

Remembered Lives

One of the few named individuals linked to the nunnery is Anna MacLean, a prioress who died in 1543. Her carved grave slab survives and is now kept in the Abbey Museum. The stone provides a rare personal connection to the women who once lived at the convent.

Although most of the nuns remain unnamed, the survival of the site itself stands as a record of their presence and contribution to Iona’s religious history.

Visiting Iona Nunnery Today

Today visitors can walk freely among the ruins of Iona Nunnery. The site lies only a short distance from the ferry and the Abbey, yet it often feels quieter and more enclosed. Low walls, open grass, and surrounding buildings create a peaceful atmosphere.

For those interested in medieval history, women’s religious life, or the quieter corners of Iona, the nunnery offers a thoughtful and rewarding visit. Its ruins remind visitors that Iona’s long spiritual story includes not only monks and saints, but also women whose lives shaped the island for centuries.

Footnote:

The founder of Iona Nunnery is referred to in historical records and sources with several spellings. His original medieval Gaelic name was Ragnall mac Somairle, while modern Gaelic often uses Raghnall mac Somairle. English-language sources typically Anglicise his name as Ranald, which is why this spelling appears in many guides and encyclopedias. All three refer to the same person, son of Somerled, and founder of the nunnery.