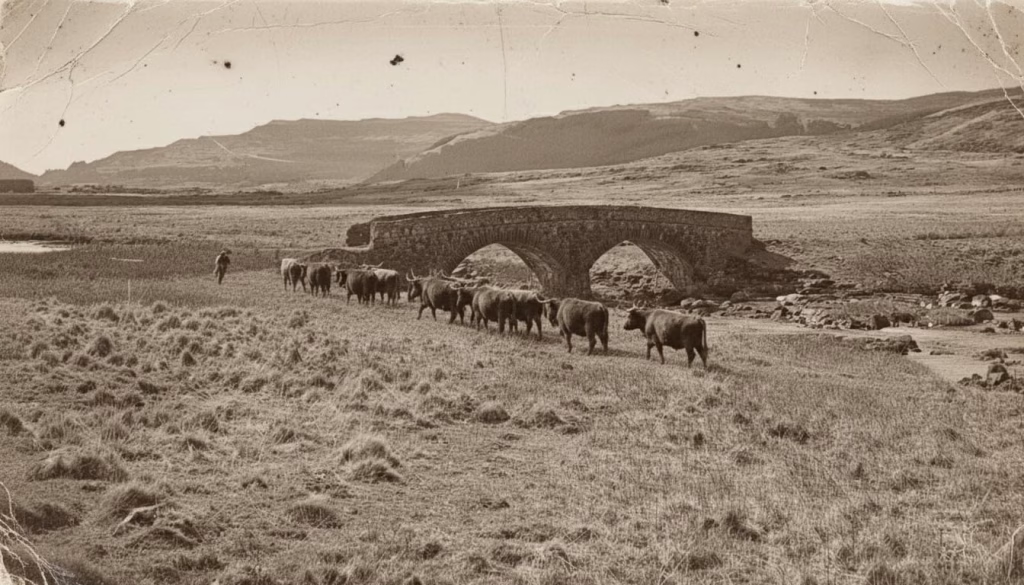

When traveling across the spectacular Isle of Mull, the scenic drive to the historic ferry port of Fionnphort and the sacred island of Iona often brings moments of quiet reflection. Photographers frequently capture one such spot, the picturesque crossing at the head of Loch Beg, and nature lovers cherish it. While many visitors pause here to take in the serene landscape, few realize they observe more than just a charming bridge; they are seeing a vital piece of Scottish history. This 18th-century marvel of civil engineering underwrote the entire Ross of Mull economy for nearly two centuries.

To clarify the nomenclature for visitors, this historical landmark is commonly known by its scenic location as the Loch Beg Bridge, but Historic Environment Scotland officially designates it as the Old Kinloch Bridge. The structure is located at Kinloch. It spans the River Coladoir before the river empties into Loch Beg, an inlet of the expansive Loch Scridain. We will refer to the structure as both Loch Beg Bridge and Old Kinloch Bridge throughout this article. If you seek out the true historical heart of Mull, this quiet riverside location, situated near Pennyghael, offers a profound and tangible connection to the island’s demanding past.

The Strategic Necessity: An Unavoidable Crossing

The bridge’s geography roots the historical importance of the Kinloch crossing. This location is not just a route to the south of the island; it is, quite definitively, the only continuous overland route providing vehicular access to and from the entirety of the Ross of Mull peninsula and the spiritual island of Iona beyond.

For centuries, this singular corridor served communities in the parishes of Kilfinichen and Kilvickeon. Their trade, communications, and accessibility depended absolutely on a guaranteed crossing over the River Coladoir. Losing this bridge, or relying on a ford that a Highland storm could render impassable, effectively severed the southern half of Mull from the rest of the island. The construction of a robust, permanent structure here was not a luxury; it was a primary strategic imperative. The people responsible for its creation understood that investment in a high-quality, fixed crossing was essential for economic survival, regardless of external funding streams.

Today, the site vividly presents two eras of island transport. The modern, three-span concrete crossing carries the main artery, the A849, accommodating the volume and speed of contemporary life. Yet, standing slightly downstream, bypassed and preserved, is the original stone bridge. It remains a patient testament to the engineering standards of a bygone age.

Architectural Riddle: The Shadow of Thomas Telford

Built sometime in the Late 18th Century, the Old Kinloch Bridge (formally listed as LB17947) is classified as a handsome stone arch bridge. It features two segmental arches supported by a thick central pier set directly in the riverbed. Its material is durable rubble stone, the standard for enduring Highland construction of the era.

However, this bridge is much more than simple rustic construction. It possesses sophisticated design elements that immediately raise the question of its creator. These elements place it in the orbit of Scotland’s most famous civil engineer, Thomas Telford.

Engineering Excellence and Telford’s Standards

Evidence of Engineering Excellence

The structure exhibits several features commonly associated with the advanced standards established by Telford during his work with the Highland Roads and Bridges Commission (HRBC):

- The Hump Backed Profile: The bridge arches slightly over the central pier. This design maximizes clearance below, enhancing its resistance to the powerful floods common to the Coladoir River.

- Battered Abutments and Curved Parapets: The abutments slope inward for immense stability. The parapets curve smoothly at the ends, melding into the embankment. This attention to detail provided enhanced structural integrity and longevity. These features were hallmarks of Telford’s standardized engineering specifications.

Despite the strong architectural correlation, the historical record presents a fascinating paradox. While Thomas Telford was deeply involved in planning road infrastructure on Mull, contemporary accounts confirm that “local politics” blocked actual road construction by the HRBC. This means the bridge, which looks and performs like a Telford design, was built on an island where political issues impeded the great engineer’s official commissions.

The Old Kinloch Bridge, therefore, is not a direct government commission; it is a sterling example of architectural adoption. Local land proprietors, road trusts, or supervising surveyors must have intentionally recognized and implemented the most reliable and advanced engineering specifications available at the time. Telford’s standards, even without central funding or oversight. The bridge’s exceptional quality and its two-century operational life serve as a powerful monument to the skill and independent spirit of the local craftsmen who built it.

Economic Engine: The Droving Clue

To truly understand the Old Kinloch Bridge, we must look beyond its elegant arches and consider its primary cargo: cattle.

The bridge’s construction happened during a period when the Highland economy vitally engaged in the cattle droving trade. This lucrative trade saw drovers move vast herds of livestock across Scotland to supply booming markets to the south. The Ross of Mull, with its grazing lands, was a critical collection area. The cattle needed to move north toward ferry crossings, such as those at Salen or Grass Point.

Droving was a demanding and risky enterprise. It required guaranteed river crossings. A secure, permanent bridge eliminated the delays and potential losses associated with dangerous fords, especially during high water. Its role in ensuring the consistent flow of the island’s most valuable export economically justified the high cost of building this sophisticated stone structure.

The physical design of the bridge confirms its role in the droving era. Unlike modern roads designed for wide, two-way traffic, the Kinloch Bridge is restrictively narrow. The width between the parapets measures only 3.0 metres. This dimension perfectly suited the sequential movement of large herds of livestock or single-file carts used by drovers, who prioritized strength and durable passage over vehicular capacity.

This narrow gauge is perhaps the most telling feature of the bridge. It is a silent indicator that the dominance of the livestock trade set its design parameters. The bridge was built to move beasts to market, solidifying the wealth and structure of the 18th-century island economy.

Legacy and Retirement

For nearly 200 years, the Old Kinloch Bridge stood firm as the primary lifeline for the Ross of Mull. Its enduring performance is noteworthy. A search through general engineering records reveals no mention of the bridge suffering catastrophic collapse due to flooding or failure. The structure was ultimately retired not because it failed, but because its design, built for the needs of cattle and single carts, became functionally obsolete for the demands of 20th-century motor traffic.

By the second half of the 20th century, the volume and weight of vehicles on the A849 increased. The narrow 3.0-meter span could no longer meet safety and logistical standards. Authorities commissioned the New Bridge, a contemporary concrete structure with wider safety verges, to bypass the old arch.

Fortunately, people recognized the Old Kinloch Bridge’s historical value in time. In 1971, it was formally protected as a Category B Listed Building, ensuring the preservation of this crucial piece of Mull’s transport heritage.

Today, the Old Kinloch Bridge carries only a quiet, unclassified track. Its function has shifted from an economic artery to a peaceful, historic monument. It invites visitors to pause and appreciate the rustic charm and the serene landscape of Loch Beg, offering a genuine moment of stepping back in time.

Visiting the Loch Beg Bridge

The Kinloch Bridge is a must-see site for anyone touring the Isle of Mull, particularly those heading to the ferry port of Fionnphort and the sacred island of Iona.