Defiance defines Carsaig House. Situated at the very terminus of a treacherous single-track road on the south coast of Mull, it stands as a solitary bastion against the Atlantic elements. Unlike the sheltered mansions of the island’s interior, builders specifically designed Carsaig to face the full fury of the ocean. It sits within a natural amphitheatre of basalt cliffs that rise hundreds of feet behind the roof, creating a setting that appears both protective and overwhelming.

Consequently, the architecture of the house reflects this dramatic location. Masons built the walls using dark, local volcanic stone, presenting a formidable silhouette to visitors. Instead of the delicate ornamentation of the Georgian era, the design favours a robust, almost martial style. With its heavy masonry, slate roof, and commanding position above the black sands of the bay, Carsaig House looks less like a holiday home and more like a fortress designed to withstand a siege by the sea itself.

The Pennycross Legacy

To understand the house, you must first understand the family that claimed this wild territory. The Macleans of Pennycross, a powerful cadet branch of Clan Maclean, held these lands for generations. For centuries, they managed the estate from earlier, more modest dwellings, acting as the administrators and military leaders of the Ross of Mull. Even today, the name “Pennycross” permeates the island’s history, synonymous with the stewardship of this rugged coast.

However, the Victorian era brought a shift in the family’s fortunes and preferences. In the late 19th century, the Macleans made the significant decision to relocate their primary seat. Archibald Maclean of Pennycross constructed a new residence, Innimore Lodge, further east along the cliffs. This move left the original Carsaig site open for a new chapter. The transition marked the end of the house serving purely as a clan stronghold and the beginning of its evolution into a grand sporting estate and country retreat.

The Victorian Transformation

The structure that stands today is largely a product of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Following the Maclean departure, the estate was sold, bringing with it the wealth and architectural ambitions of the industrial age. The property was acquired in 1893 by Colonel George Wells Cheape, a well-known figure in Fife who also owned the nearby Tiroran estate (Source: Historic Environment Scotland LB12301). Colonel Cheape possessed a deep passion for the Highlands and maintained Carsaig as a residence that matched the grandeur of the scenery.

Under this new ownership, the house was solidified in the Scottish Baronial style, a revival movement that romanticized the castles of the Middle Ages. The design features crenellated walls that mimic battlements, crow-stepped gables, and a layout designed to accommodate the large staff required to run such an isolated household. Craftsmen fitted the interior with the heavy timber panelling and large fireplaces essential for comfort in a location where the winter gales batter the windows for weeks on end.

Built from the Cliffs

Carsaig House is literally a product of its environment. Masons constructed the very walls of the building from the famous Carsaig sandstone and the volcanic basalt found on the estate. This choice represents a significant historical link, as builders used this same stone to restore Iona Abbey in 1874. Thus, the connection between the house and the holy island remains physical and enduring.

Building such a substantial mansion in this remote location proved a logistical feat. In an era before modern road haulage, ships had to transport any materials that workers could not quarry on site. As such, the estate relied on the massive stone pier, which the engineer Joseph Mitchell built in 1850, to receive supplies. Coal for the fires, furniture for the drawing rooms, and fine goods from the mainland all arrived via the dangerous currents of Carsaig Bay. In essence, the house functioned as an island upon an island, dependent on the maritime link for its survival.

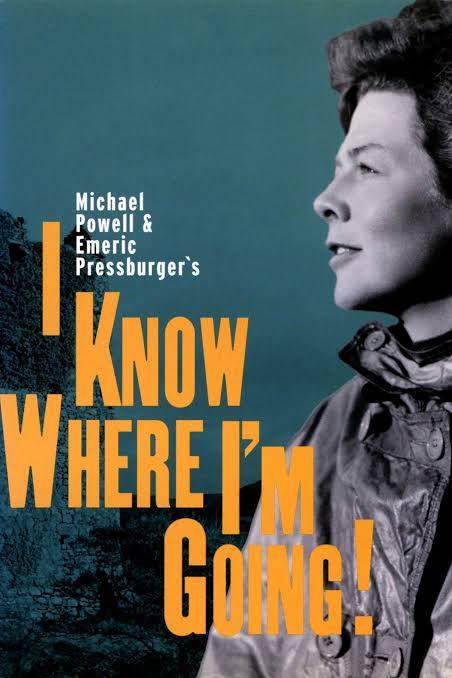

The House on Film

While many Highland houses have history, few possess the cinematic pedigree of Carsaig. In 1945, the house became a central character in the Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger film, I Know Where I’m Going!. The directors sought a location that embodied the mystical, untamed nature of the Hebrides, and they found it in the silhouette of Carsaig House.

In the film, the script renames the house “Erraig House,” and it serves as the home of Catriona Potts. The production team used the exterior of the house effectively to convey the isolation of the characters. Notably, the shots of the storm lashing against the windows and the characters struggling against the wind in the garden were not special effects; instead, they captured the reality of life at Carsaig. The house provided the gothic, romantic backdrop that grounded the film’s folklore elements in reality. To this day, film historians consider the house’s presence in the movie to be one of the most atmospheric depictions of a Scottish estate ever captured on screen.

A young Englishwoman goes to the Hebrides to marry her older, wealthier fiancé. When the weather keeps them separated on different islands, she begins to have second thoughts.

Life in Isolation

Living at Carsaig House has always required a specific kind of resilience. Drivers widely consider the road to the house one of the most challenging on Mull, as the steep, twisting descent cuts the property off from the rest of the world. For the Victorian owners, this isolation necessitated a high degree of self-sufficiency. Consequently, the house had to function as its own community.

Even the walled garden, which still sits between the house and the sea, served a practical purpose rather than a merely ornamental one. High stone walls protected the beds from salt spray, allowing the garden to provide vital fresh produce. Meanwhile, the estate maintained its own dairy, laundry, and power generation systems long before the grid reached this far south. The architectural layout of the house, with its distinct servant wings and extensive cellars, tells the story of this necessary independence. It was a place where staff had to keep the larder full and the coal bunker stocked, for a winter storm could easily sever the link to civilization.

The Modern Restoration

In the 21st century, the current owners saved Carsaig House from the decline that claimed so many other remote mansions. The Macphail family currently owns the property and has undertaken the immense task of restoring the fabric of the building. Maintaining a Victorian stone structure in the face of constant salt erosion and gale-force winds is a perpetual battle, yet the house remains in remarkable condition.

Today, the interior of the house balances the preservation of its history with modern comfort. The grand library, wood-panelled reception rooms, and sweeping staircases still boast the antiques that give the house its soul, yet the owners have carefully updated the draughty reality of 19th-century living for 21st-century guests. The house now operates as an exclusive holiday let, allowing visitors to experience the “Pennycross” lifestyle. It stands as a rare example of a working Highland home that successfully transitioned from a clan stronghold to a modern sanctuary, without losing the rugged character that defines it.