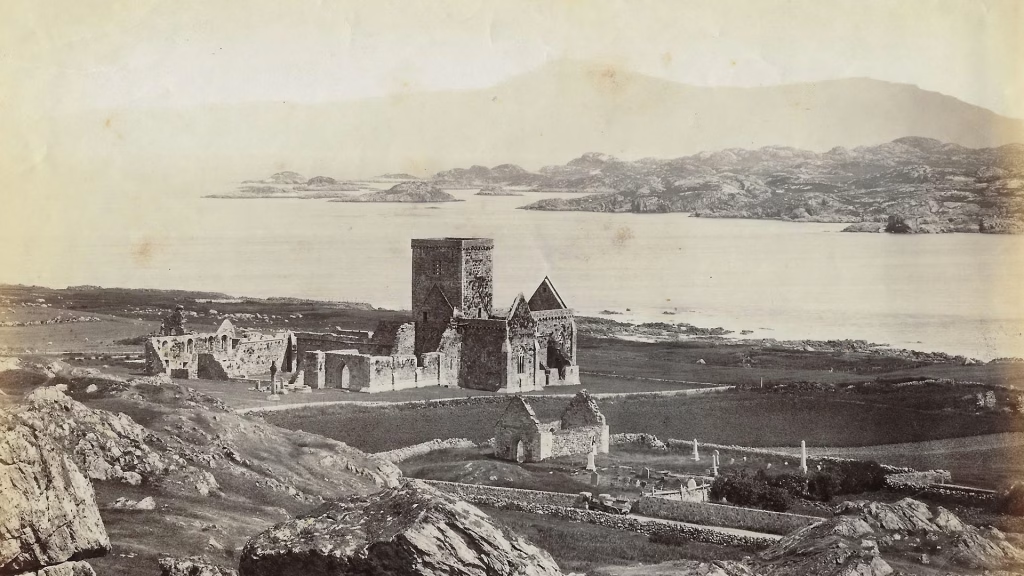

The tiny island of Iona lies off the southwest tip of the Isle of Mull, separated from its larger neighbor by a mile of turquoise water. Although the island measures barely three miles in length, its influence on Scottish history and spirituality remains immeasurable. Iona Abbey dominates the island’s skyline, standing firm against the Atlantic winds.

This site has served as a beacon of worship, art, and political power for nearly 1,500 years. Known as the “Cradle of Christianity” in Scotland, many describe it as a “thin place” where the physical and spiritual worlds meet. But the stone building you see today represents only the latest chapter in a turbulent history of exile, Viking raids, royal burials, and a remarkable 20th century resurrection.

The Arrival of St Columba (563 AD)

The story does not begin with the visible stone church, but with a simple wooden monastery from the 6th century. An Irish monk named Columba (Colum Cille) arrived on Iona in 563 AD with twelve companions. Historical accounts describe Columba as a man of high noble birth in Ireland who left his homeland as an exile. Most historians attribute this departure to his involvement in the bloody Battle of Cúl Dreimhne in 561 AD.

Columba sought a location to establish a new monastic foundation, and he did not choose Iona by accident. The island sat on the strategic border between the Scots of Dál Riata and the Picts, providing an ideal base for his missionary work. He landed at the southern bay now known as St Columba’s Bay.

Upon arrival, Columba established a monastery. Crucially, none of the stone buildings standing today date from Columba’s time. He constructed his monastery of timber, wattle, and daub, consisting of a small church, individual cells for the monks, and communal buildings. Additionally, the entire settlement was enclosed by an earthen bank or vallum.

Archaeologists have found evidence of these early structures, specifically on the small hillock known as Tòrr an Aba (The Abbot’s Hill) directly in front of the current Abbey. The findings revealed a writing hut that likely belonged to Columba himself. From this modest base, Columba and his followers launched a massive mission to convert the Picts of Scotland and the people of Northern England to Christianity.

The Golden Age and the Book of Kells

Iona did not fade into obscurity after Columba died in 597 AD. On the contrary, it grew into a vital intellectual and artistic center. Between the 7th and 8th centuries, the monastery produced incredible works of insular art. The monks worked as master metalworkers and sculptors to create the iconic “High Crosses.” These huge free standing stone crosses featured intricate biblical scenes and Celtic knotwork, used to teach the Bible to a largely illiterate population.

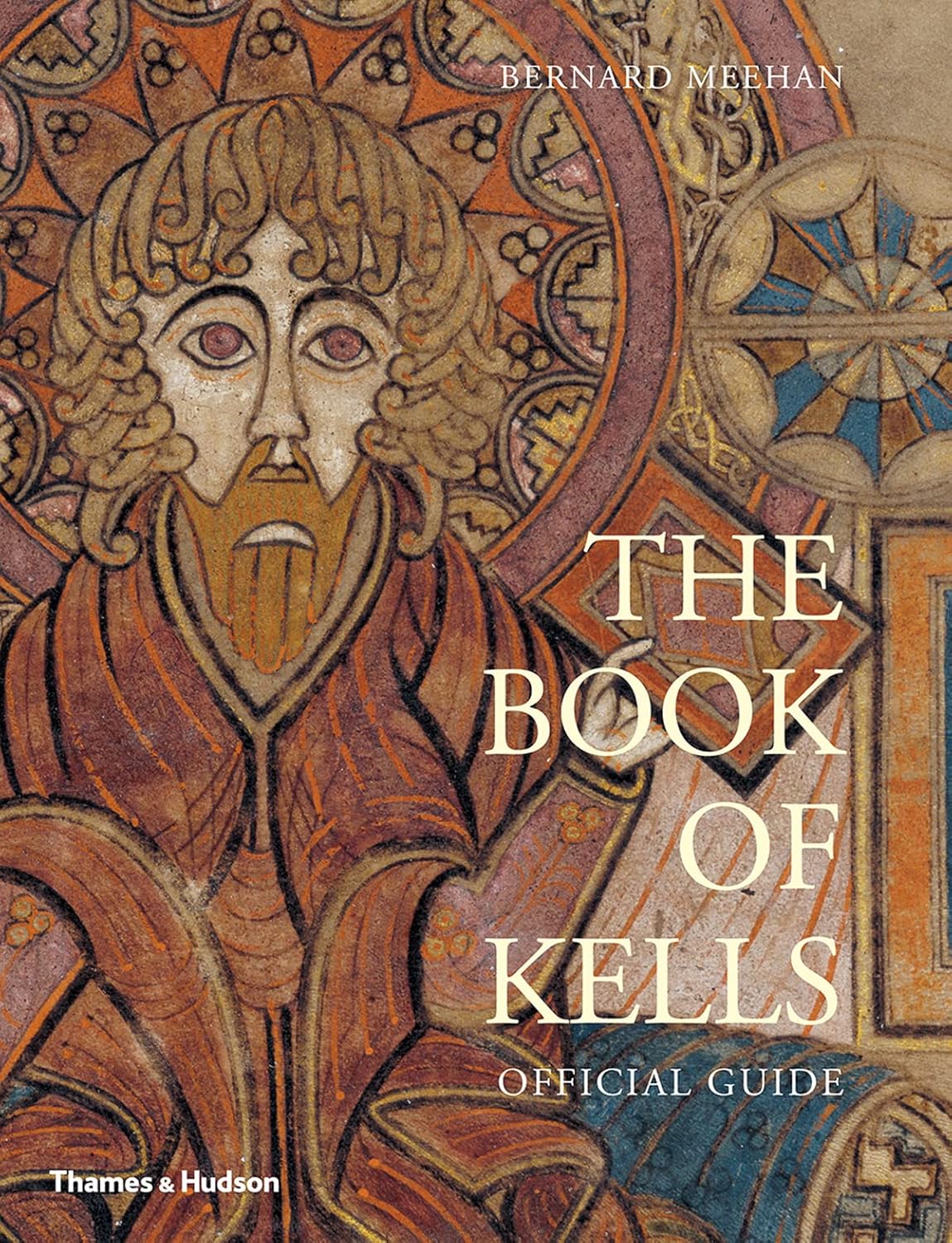

Scholars widely believe Iona gave birth to the Book of Kells. This illuminated manuscript contains the four Gospels of the New Testament and is famous for its lavish and complex decoration. While the book takes its name from the Abbey of Kells in Ireland, historians believe the monks likely started it on Iona around 800 AD.

They probably moved the manuscript to Kells later to protect it from the increasing threat of Viking raids. Ultimately, that decision saved one of the world’s greatest medieval treasures. The artistic output of this era defined the visual style of Christianity in the British Isles for centuries.

The Book of Kells, dating from about 800, is a brilliantly decorated manuscript of the four Gospels. This new official guide, by the former Keeper of Manuscripts at Trinity College Library, Dublin, provides fascinating insights into the Book of Kells, revealing the astounding detail and richness of one of the greatest works of medieval art.

The Viking Onslaught

Iona’s wealth and fame eventually attracted unwanted attention. Because the island sits on a major sea lane, it became an easy target for Norse raiders expanding their reach from Scandinavia. The first Viking raid struck Iona in 795 AD, beginning a terrifying century for the monks where attacks proved brutal and often deadly.

The most infamous attack occurred in 806 AD when Viking raiders massacred 68 monks in a single day at a small bay north of the village. Locals know this spot as Martyrs’ Bay to this day. Despite the danger, some monks remained, though tragedy struck again in 825 AD when raiders martyred St Blathmac for refusing to reveal the hiding place of St Columba’s jeweled reliquary shrine.

These relentless attacks eventually forced the community to retreat. They divided the relics of St Columba for safekeeping, moving some to Kells in Ireland and others to Dunkeld in mainland Scotland. Although the great light of Iona dimmed by the mid 9th century, a small community of monks stubbornly held on.

The Benedictine Abbey (c. 1200)

The stone abbey visitors see today represents a completely different era. After centuries of Norse control over the Hebrides, power eventually shifted to Somerled, known to history as the legendary “King of the Isles.” His son, Reginald (Ranald), invited the Benedictine order to the island around 1200 AD to establish a new monastery on the site of Columba’s old community. This marked a major transition as the region shifted from the Celtic church tradition to the Romanized continental style.

Reginald also founded an Augustinian Nunnery south of the Abbey, and its ruins remain some of the most beautiful on the island. The Benedictine monks built in stone, creating the core of the Abbey church, the cloisters, and the chapter house. Notably, the architecture from this period mixes Irish, Romanesque, and Gothic styles, reflecting the island’s unique position at the crossroads of the Irish Sea.

The Benedictine Abbey thrived as a place of pilgrimage for the next 350 years. However, the Protestant Reformation of 1560 brought monastic life to an abrupt end. The reformers dispersed the monks and cast down the mesmerizing high crosses. Legend claims they destroyed 360 crosses, and while this number likely exaggerates the truth, the great stone buildings fell into ruin.

Reilig Odhráin: The Graveyard of Kings

Adjacent to the Abbey, you will find Reilig Odhráin (St Oran’s Cemetery). This site predates the Benedictine foundation and steeps the island in royal history. Tradition claims this small graveyard holds the remains of 48 Scottish kings, 8 Norwegian kings, and 4 Irish kings. While modern historians caution that medieval chroniclers likely inflated these numbers to enhance Iona’s prestige, historical fact confirms Iona as the burial place of the Dál Riata kings and their successors.

Famous monarchs linked to the site include Kenneth MacAlpin (died 858), the first King of a united Scotland, and Macbeth (died 1057), who was made infamous by Shakespeare although the real historical figure differed greatly from the play. Duncan I, whom Macbeth defeated, lies here as well.

The cemetery also houses many Clan Chiefs, with graves for the MacKinnons, MacLeans, and MacLeods. In addition, John Smith, the leader of the UK Labour Party who died in 1994, is buried here, continuing the tradition of Iona as a place of honor.

In the center of the graveyard stands St Oran’s Chapel. Likely built by Somerled in the 12th century, it remains the oldest intact building on Iona. It features a simple, Romanesque arched doorway and an interior with a hauntingly distinct acoustic.

Ruins to Resurrection: The Iona Community

By the 19th century, Iona Abbey stood as a romantic ruin, roofless and battered by the elements. Although the Iona Cathedral Trust began some stabilization work in 1899, the true resurrection occurred in the 20th century, driven by a man named George MacLeod. A charismatic minister from Govan, Glasgow, MacLeod had fought in World War I and was haunted by both the poverty in Glasgow and the futility of war. He sought a new way to live out the Christian faith.

He founded the Iona Community in 1938 with a radical idea: bringing together trainee ministers and unemployed shipwrights from Glasgow to rebuild the ruined monastic quarters of the Abbey. This project served as a social experiment, forcing intellectuals and laborers to live, work, and worship together.

They succeeded against the odds. Over several decades, they fully restored the cloisters, the refectory, and the living quarters. These buildings do not function as a museum today. Instead, they serve as a living center run by the Iona Community, hosting guests from around the world for weeks of community living and peace building.

Exploring the Site Today

Historic Environment Scotland manages the site today, allowing you to walk through layers of history when you visit. First, you will see St Martin’s Cross standing outside the West door. Carved from a single slab of epidiorite in the 8th century, it remains the only high cross to stand in its original spot for over 1,200 years. The west face depicts the Virgin and Child alongside Daniel in the lion’s den. A replica of St John’s Cross stands nearby, while the original resides in the Abbey museum after being smashed by a storm.

The interior of the Abbey Church blends the medieval and the modern. The stone walls date mostly from the 13th and 15th centuries, but the wooden roof is modern. The Communion Table uses polished green Iona marble quarried from the south end of the island.

The square cloister garden features restored domestic buildings on all sides, with a modern sculpture titled The Descent of the Spirit by Jacob Lipchitz sitting in the center. Furthermore, you should inspect the capitals of the cloister columns closely. Although many are modern carvings, they follow the medieval tradition by depicting local flora, fauna, and whimsical birds.

The museum sits in the old Infirmary behind the Abbey. It houses Scotland’s finest collection of early medieval carved stones, including original fragments of the High Crosses and huge “warrior stones” that once covered the West Highland chieftains.

Essential Facts for Visitors

Visitors need to know a few practical details. You locate the Abbey on the Isle of Iona in the Inner Hebrides, Scotland, accessed via a passenger ferry from Fionnphort on the Isle of Mull. Importantly, the island does not allow visitor cars. The site opens year round, although hours reduce during the winter months.

Historic Environment Scotland cares for the historic fabric, while the Iona Community runs the residential quarters. The Abbey church functions as a working place of worship. Therefore, the community holds daily services, usually in the morning and evening, welcoming all members of the public regardless of faith.

The Enduring Legacy of Iona

Iona Abbey serves as more than just a tourist attraction; ultimately, it stands as a testament to survival. The site evolved from the fragile timber cells of St Columba to the stone permanence of the Benedictines, followed by George MacLeod’s modern revitalization. The Abbey has constantly reinvented itself through these eras, yet it remains true to its purpose.

You might feel drawn by the history of the Vikings or the Book of Kells, or perhaps the mystery of the Scottish kings interests you. You may simply seek the peaceful atmosphere of the “Holy Isle.” In every case, Iona offers a profound connection to the past. It remains a place where people find clarity at the edge of the world.