In the shifting waters between the Isle of Mull and Lismore lies a jagged skerry known as Lady’s Rock. Passing vessels see it merely as a navigational hazard. However, to those who know its past, it marks the spot where a murder failed. This is the true tale of a planned execution by sea, a survivor whose silence spoke volumes, and the legacy left in the waves between two of Scotland’s most powerful clans, the Macleans and the Campbells.

A Dangerous Outcrop in the Sound

Lady’s Rock sits southeast of the island of Lismore, fully exposed at low tide yet completely submerged at high water. Today, the Northern Lighthouse Board maintains a navigational beacon there, warning mariners to steer clear. To the southwest, the towers of Duart Castle rise on the headland of Mull, keeping silent vigil over the waters. Furthermore, local sailors have long respected this stretch of sea, narrow, tidal, and filled with undercurrents, while the unwary fear it.

Clans in Conflict: The Macleans of Duart and the Campbells of Argyll

The 16th century was an age of Gaelic nobility, coastal raiding, strategic marriages, and dangerous truces. The Macleans ruled as the dominant family on Mull, holding Duart Castle and controlling shipping routes through the Hebridean straits. Meanwhile, the Campbells of Argyll, powerful stewards of mainland Scotland, were ascending in both politics and influence. Their interests overlapped in trade and military reach; consequently, marriage sometimes united them, though suspicion often divided them.

When Lachlan Cattanach Maclean of Duart, the clan’s eleventh chief, married Lady Catherine Campbell, sister to the Earl of Argyll, the families intended the union to quiet rivalries. But beneath its political usefulness, tensions festered. Contemporaries knew Lachlan for his fierce temper and ruthlessness. Some accounts from later generations describe physical abuse or emotional cruelty. Conversely, others suggest Catherine herself was no passive victim. Regardless, the marriage remained unstable, and eventually, one party sought a deadly resolution.

The Abandonment on the Rock

Reportedly, sometime in 1527, Maclean took his wife out to sea and abandoned her on Lady’s Rock as the tide receded. Although history has lost the exact time of year, tradition holds it was a calm night. At low tide, the sea reveals the skerry for several hours before rising again. Alone, with no food, water, or means of calling for help, Lady Catherine faced almost certain drowning when the tide returned. Moreover, no witnesses appeared, only the tide chart, the man who rowed her there, and the intentions he tried to conceal.

Rescue and Revelation

By morning, Maclean scanned the rock from Duart Castle and saw nothing. Assuming his plan had succeeded, he immediately sent riders to Inveraray to inform the Campbells of Catherine’s “accidental” death. According to tradition, the Earl of Argyll received the message but said nothing. Later, when Lachlan traveled to offer condolences and claim grief, the Campbells welcomed him into Inveraray Castle’s great hall. There, shockingly, Lady Catherine sat alive at the head of the table. Passing fishermen had rescued her during the night, acting either on chance or under secret orders from her brother.

The Death of Lachlan Maclean

Two years after the failed murder, in 1529, assassins killed Lachlan Maclean in Edinburgh. Someone stabbed him in his bed, reportedly at the order of Catherine’s brother, the Earl of Argyll. Authorities never brought official charges. Consequently, his death passed into the historical record quietly. Yet, among the Campbells, the family viewed it as justice. Among the Macleans, however, it served as a warning about allying with Argyll.

The Legend Grows

Eventually, the story of Lady’s Rock spread across the Hebrides. Gaelic poets turned it into verse, while campfire tales told of the abandoned lady raising her shawl to the moon. In Lismore, children whispered that the wind still carried her voice. At Duart, the clan suppressed the tale in official histories for a time, but the people never forgot it.

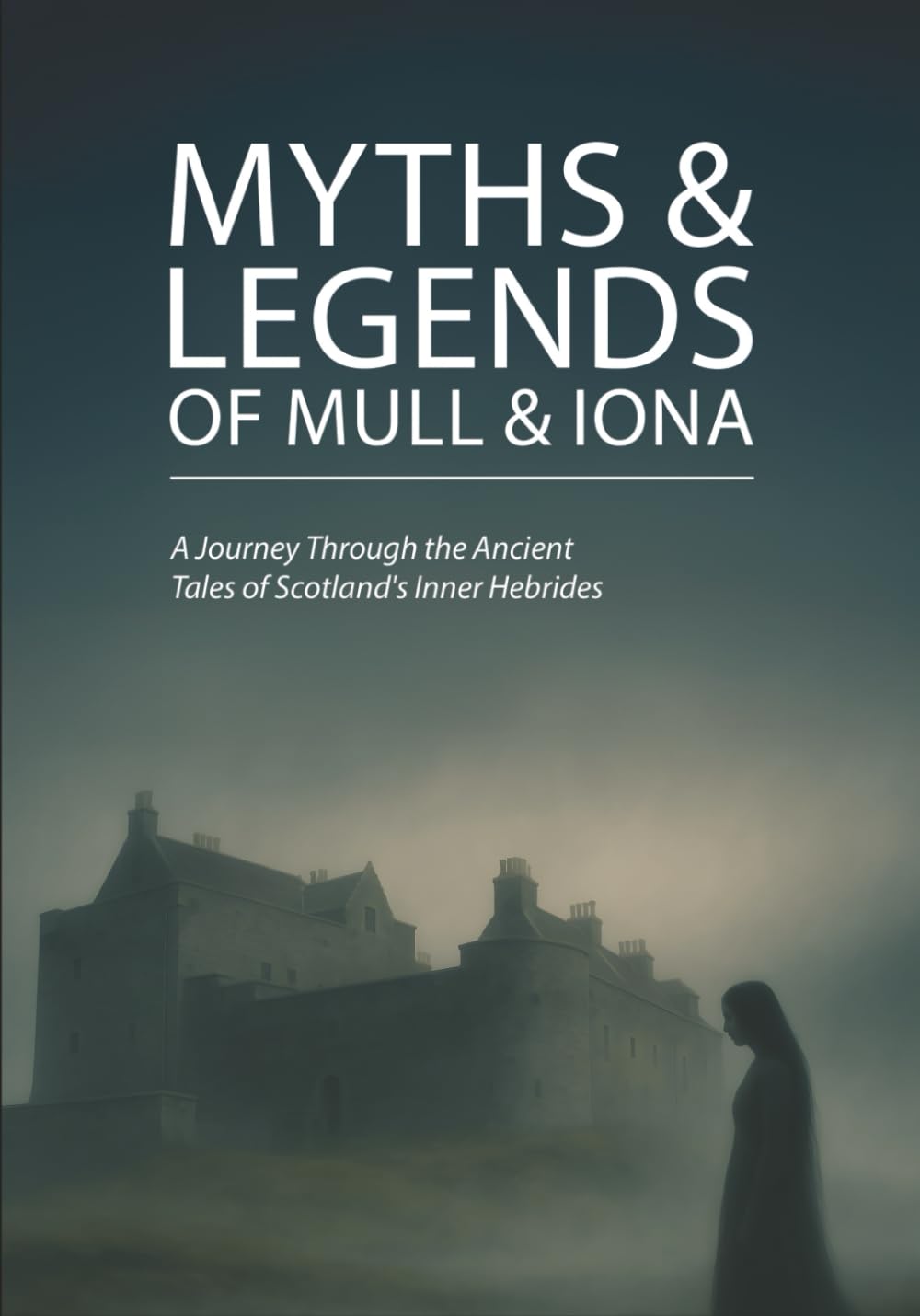

Step into a world where ancient legends breathe and history whispers from every stone. This enchanting book invites you on a captivating journey through the heart of Scotland's Inner Hebrides, a land steeped in magic and timeless tales.

Variations and Alternative Theories

Admittedly, not all versions of the story agree on the details. Some argue that Maclean placed Catherine on the rock fully aware that help waited nearby. Others believe that Maclean did not intend her death but meant only to frighten her. Furthermore, a few 19th century romantic histories suggest the Campbells fabricated the whole affair to justify revenge. Nevertheless, contemporary clan records confirm an attempted murder and retribution in kind. The consistency of location, individuals, and consequence lends significant weight to the traditional version.

Duart Castle’s Place in the Tale

Standing on a promontory overlooking the rock, Duart Castle holds more than strategic views; it anchors the narrative. Following restoration in the 20th century, the castle remains open to the public, and its walls bear plaques and displays referencing the infamous rock across the water. Today, visitors stand on the ramparts and see what Lachlan may have seen that morning, a rising tide, a vanishing figure, and the illusion of success.

The Navigational Beacon and Modern Use

In the 20th century, the Northern Lighthouse Board erected a beacon atop Lady’s Rock. They automated the solar powered light, and all marine maps now chart its location. Although it serves a practical function, its presence atop a place of attempted murder feels jarring. From certain angles, the beacon seems less a warning to sailors than a vigil for a woman who refused to drown.

Cultural Legacy and Symbolism

Lady’s Rock has endured as more than a footnote in clan history. Instead, it represents survival, defiance, and the power of place in Scottish storytelling. For the Campbells, it affirms justice and endurance. Conversely, for the Macleans, it marks a cautionary tale of ambition turned inward. In Scottish tourism, guides often mention it as a scenic curiosity, but to those who study its past, it remains a stone of significance and shadow.

A Place of Memory

Boats that pass through the sound sometimes linger by Lady’s Rock. Guides may lower their voices and point quietly. Similarly, photographers come at low tide to capture its stark isolation. On windless days, the rock appears almost pretty, ringed by kelp and sea birds. Yet, on stormy ones, it becomes a silhouette against the whitecaps, bare and unyielding. It is the kind of place where a person can feel history even without knowing the details.

With Other Papers from the Breadalbane Charter Room (Classic Reprint) Paperback – 21 April 2018.

by Cosmo Nelson Innes (Author)

Historical Sources

The tale appears in several documented sources, including:

- The Black Book of Taymouth

- Campbell family genealogies compiled in the seventeenth century

- Later references in Sir Walter Scott’s notes and Highland travelogues

- Nineteenth century gazetteers of Argyll and the Hebrides

- Modern publications on Scottish clan warfare and feuds

Final Thought

The sea forgets little, and the land even less. Lady’s Rock may not bear a plaque or monument, but it holds a chapter of Scotland’s past just the same. It stands as a warning, a survival story, and a rare moment when a woman escaped death by tide and bore silent witness to the reckoning that followed. Therefore, the next time the waters fall away and the skerry shows its face, remember what it once carried, not just stone, but justice that men denied and time reclaimed.