The Isle of Mull is not just a place of rugged coastlines and windswept moors. Beneath its natural drama lies an older world, held in stories told around peat fires and passed down with the salt air. These tales are more than curious legends. They are maps of local belief and memory, rooted in real places and often sparked by real events. Mull’s folklore survives not in dusty books, but in the way travellers pause in a glen or islanders glance toward a certain rock. The line between history and story here is as thin as mist on the Sound.

1. The Witches of Mull

In the traditions of Mull, witches were not always feared. Often they were respected women with knowledge of healing, weather, and the ways of nature. While mainland Scotland burned with witch trials, the island’s isolation gave space for different understandings. The most famous of these figures is the Dòideag, a wise woman said to have lived near Tobermory during the late sixteenth century. She was known for her foresight and was consulted by locals in matters both practical and personal.

In 1588, a galleon from the Spanish Armada anchored in Tobermory Bay. Aboard was a Spanish noblewoman who is said to have fallen in love with a man from Mull. But the man was already married. His wife, jealous and enraged, sought help from the Dòideag. What followed is part of Mull’s darker maritime lore. The ship was destroyed by an explosion and sank with all hands and its treasure. Some say the witch called down fire upon the galleon in vengeance. Others claim it was sabotage or accident. Whatever the truth, the wreck has never been conclusively identified, and treasure hunters still search beneath the bay’s silt and seaweed.

The Dòideag’s legacy has outlasted the wreck. Unlike the fearful image painted elsewhere in Europe, Mull’s witches often acted as guardians and midwives. Locals tell of women who could quiet a storm with a whispered charm or draw sickness out of a child using herbs and song. To this day, weathered stones mark where some of these women lived. Their stories are quiet now, but not forgotten. On certain nights, some say you can still hear a whisper in the wind above Tobermory, calling down a storm or carrying a warning.

2. The Headless Horseman of Glen More

Glen More is a broad, striking valley that cuts across the Isle of Mull from east to west. Travellers heading from Craignure toward Bunessan or Iona pass through it, often unaware of the legend tied to its windswept stillness. The glen shifts with the seasons. It is lush and inviting in spring and harsh and echoing in winter. Somewhere within its expanse lies one of the island’s oldest supernatural tales.

In the 16th century, the Maclaine clan ruled from Lochbuie. Their chieftain, Iain Og, had a son named Ewen, known as Eoghann a’ Chinn Bhig, “Ewen of the Little Head,” who lived with his wife on a crannog in Loch Sguabain. She was a MacDougall of Lorne, known as the Black Swan, renowned for her ambition and dissatisfaction with her place. Her hunger for status drove Ewen to seek greater holdings from his father.

Denied his claim, Ewen’s frustration hardened into open conflict. In 1538, a mass duel was arranged in Glen More. It was father against son, each accompanied by a body of followers. But legend says that on the eve of the fight, Ewen came upon a spectral washerwoman at a burn. When he asked her about his fate, she warned that if his servant failed to place the butter on the table at breakfast, he would not survive the day.

The next morning, the butter was missing. Whether out of pride or inevitability, Ewen rode into the glen. During the clash, one of Iain Og’s men rose from a rock and struck Ewen’s head clean off with a claymore. His horse bolted in terror, carrying the headless body for several miles until it came to a stop above the Lussa burn.

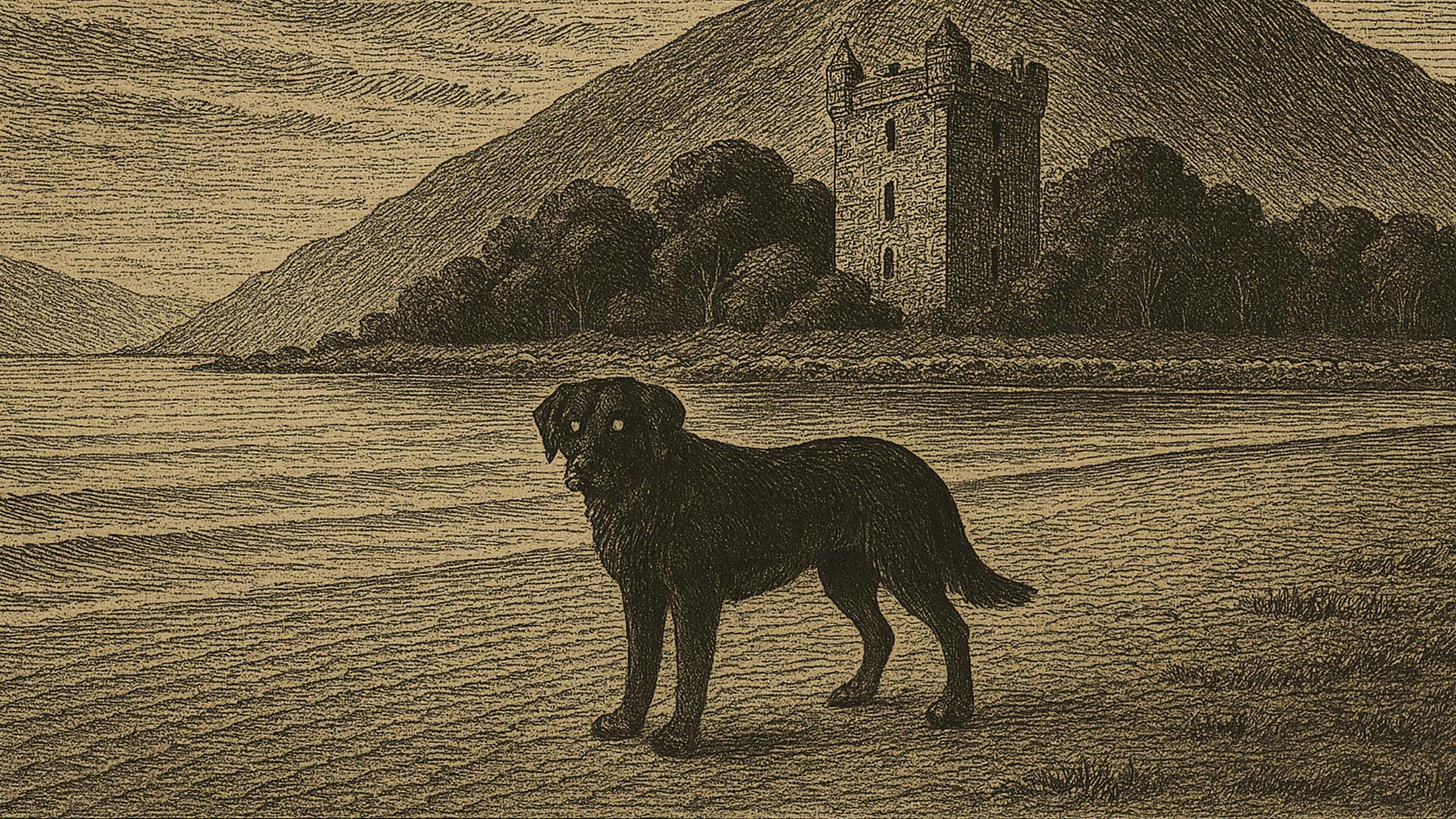

Ewen’s men buried the body temporarily on the hillside and marked it with a small cairn. They returned later to retrieve it and carried him to Iona for a proper burial. Some say his hunting dog was so traumatised at the sight of its master’s remains that it shed every hair from its body.

To this day, Ewen’s ghost is said to gallop through Glen More at dusk, appearing on a black horse with no head upon its shoulders. The sound of hooves circling Moy Castle near Lochbuie is considered an omen, a harbinger of death within the Maclaine line. The cairn where the body first fell still exists. Its location was passed down through generations and confirmed by Seton Gordon and P. A. Macnab.

3. The Piper and the Fairy Cave

Along the south coast of Mull, beyond the cliffs at Gribun, lies MacKinnon’s Cave. It is the longest sea cave in the Hebrides and has been a place of caution for generations. Accessible only at low tide, the cave runs far into the basalt and swallows light as quickly as sound. The name itself speaks of clan history, but the story most often told is not about a chief or warrior. It is about a piper who tested the cave and vanished into the dark.

This piper claimed he could walk the length of the cave while playing without pause. Some called it arrogance. Others saw it as courage. With his dog by his side and pipes in hand, he entered the cave while villagers waited outside. The music rang out clearly at first, bouncing off the stone and out to sea. Then it faded. After a few minutes, silence returned. The piper did not.

Only the dog emerged. Its fur was gone, its eyes wide. It would not go near the entrance again. Some say the fairies within the cave took the piper, angered by his intrusion. Others whisper that he crossed into another world, one that lies beneath the earth and sea. The cave remains silent now. Few venture far inside, and no one plays music there. On some evenings, when the wind shifts, the cave seems to hum. Some say it is the sound of pipes far below. Others say the cave is breathing, waiting for the next soul bold enough to enter with a tune.

4. Pennygown Chapel and the Vanishing Fairies

North of Salen lies the remains of Pennygown Chapel, a simple stone ruin half consumed by moss and silence. It once served the local community as a place of worship. Now it stands roofless, weathered by time and surrounded by stories. The most persistent of these involves a quiet pact between people and fairies, and how that trust was broken.

According to tradition, the area near the chapel was once favoured by a group of fair folk. They were said to help local crofters with small tasks. They mended torn nets, nudged lost sheep back to their flocks, and lit the way for late travellers. In return, people left gifts of bread or cream near the chapel at night. It was a relationship built on balance and silence. But one man tried to take more than was given. A fisherman, determined to catch a glimpse of the helpers, laid a trap. Whether he succeeded or not is unclear. What followed was plain. The fairies vanished.

After that night, the chapel fell out of use. No more lights flickered in the dark. No more nets were found mysteriously mended. People still walked past the ruin, but never after sunset. Children were warned not to speak within its walls. Even now, visitors report odd sensations near the burial ground. A sudden chill, a sense of being watched, or the faint sound of laughter with no clear source. Some believe the fairies moved on. Others think they are waiting. Either way, the chapel has not been reclaimed. It belongs to time and to silence now.

5. Tragedy Rock

Near the western cliffs of Gribun sits a massive boulder known simply as Tragedy Rock. The stone is not marked on every map, but it casts a long shadow in local memory. The story tied to it is one of love, loss, and the unpredictable violence of the land itself. It begins with a couple, newly wed, walking the coastline during a rising storm. They sought shelter beneath the cliffs and found it, or so they thought, under the bulk of a great rock perched above them.

No one saw what happened, but when the storm cleared, the rock had shifted. The couple was gone. Their bodies were never found. Locals climbed the slope and saw the fresh scar where stone had broken free. Flowers were left there for years after, though no formal marker was raised. The site was simply known. Visitors still stop beside the road at Gribun Head, gazing up at the slope. The rock remains where it fell, silent and enormous, half sunk in bracken and shadow. Some say the pair’s names were never recorded. Others believe they were buried there, under the stone itself, beyond reach or rescue.

Geologists confirm that the rock likely fell centuries ago. The exposed strata show signs of weathering long before the roads to Gribun were laid. But science does not explain why the story endures, passed down quietly through generations of islanders. Some call the boulder cursed. Others call it sacred. A place not to fear, but to respect. Tragedy Rock stands as a reminder that Mull’s landscape is not passive. It is alive, with a memory deeper than any map, and a silence heavy with loss.

6. The Black Dog of Lochbuie

In the remote southern reaches of Mull, beyond the dark waters of Lochbuie, locals speak of a creature that appears before sorrow. The Black Dog is not a myth in the casual sense. It is an omen. A shape that appears near the shoreline or along the road by Moy Castle when something is about to go wrong. The creature is large and silent, described as coal black with eyes that glow faintly in the half light. It does not growl or bark. It simply watches.

Accounts vary, but the essence remains. Before accidents, shipwrecks, or the death of a clan member, the dog is seen walking alone. Some tales speak of it standing on the stone walls near the old graveyard. Others say it appears just long enough to be noticed before vanishing into the grass. One nineteenth-century diary found in a local estate mentions a sighting just days before a fishing boat went down off Carsaig. Another describes the dog being seen beneath the windows of Moy during a year of sickness.

Attempts to dismiss the creature as superstition have never truly taken hold. Even modern-day residents nod when asked if the dog still appears. They may not speak of it directly, but few will walk the road near the loch at night without looking twice. The Black Dog is not seen as evil. It does not attack. Instead, it warns. It reminds those who live close to the sea and stone that Mull is older than we remember, and that not everything walks in flesh. Some walk in memory, and some walk in shadow.

7. The Ghost of Duart Castle

Perched above the Sound of Mull, Duart Castle rises from a rocky outcrop like a sentinel. It is the ancestral home of Clan Maclean, a place tied to centuries of island history. Battles were planned there. Feasts held. Alliances formed and broken. But among its long past, one story remains especially potent. The tale of a woman who never left. Her name is not always agreed upon, but her suffering is. She was a young noblewoman, married for political reasons to a Maclean chief. The match was strained from the start.

Accounts say that after a series of arguments, her husband ordered her locked in a small chamber in the tower. Days passed. Then weeks. She cried for help, but the thick stone walls gave her no audience. No one intervened. She died in silence, alone and forgotten until visitors came and found her body. Her family took her home to be buried, and vengeance between clans followed. But something of her remained. That is what the stories say.

Visitors to Duart have reported cold spots in specific rooms. Guides tell of footsteps in empty corridors and sudden weeping heard within the tower. One long-time caretaker refused to enter the chamber alone after hearing a whisper that matched no known voice. Others have seen a pale figure at one of the narrow windows, even when the tower was locked. Though the castle has been restored and opens each season to the public, it carries its history in the stone. The woman may no longer wait behind the door. But her grief, and the silence that surrounded it, lingers still.

8. Cultural Roots and Oral Tradition

Mull’s folklore is more than a set of ghost stories. It is the way an island carries its past. Before printed books and recorded histories, stories were told aloud, passed from elder to child across hearth and hillside. In these stories, the line between the natural and supernatural was not a matter of belief. It was part of the world. The wind was a voice. The moon a sign. To live on Mull was to live with uncertainty, and stories were how people made sense of the unseen.

These tales carry warnings. They teach what not to disturb, which places deserve caution, and what happens when pride crosses into arrogance. The woman who called down fire. The son who rode to his death. The dog that walks before disaster. These are not just characters. They are instructions. And even now, they continue to be told. Teachers in island schools share them as part of the local curriculum. Grandparents remind the young not to whistle at night or speak carelessly of fairy places.

What gives Mull’s folklore its strength is its geography. Every glen, cave, and standing stone is part of a living map. To tell the story is to walk the land. And once you hear them, it is difficult to see the island the same way. Each bend in the road holds a possibility. Each hill has eyes. Mull is beautiful, but never empty. Its past breathes just under the surface, in the silence between waves and the shadow that passes without sound.

9. Visiting the Sites

- MacKinnon’s Cave — Located on the Gribun coast, accessible at low tide. Visitors should wear sturdy boots and take care on wet stones.

- Pennygown Chapel — Near Salen, visible from the main road. The ruins can be visited during daylight and are open to respectful entry.

- Gribun Head — Offers dramatic views and roadside access near Tragedy Rock. There is no marked trail to the boulder, but it can be seen from the verge.

- Duart Castle — Open seasonally with guided tours. The tower chamber associated with the haunting is part of the public route.

- Lochbuie and Moy Castle — Reachable via a single-track road. The castle is partially restored, and the lochside walk is a good place to reflect on the Black Dog legend.

- Glen More — The main road from Craignure to Fionnphort runs through the glen. Look for the stretch near Loch Sguabain and imagine the site of the MacLaine duel.

- Tobermory Bay — The waterfront has interpretive signs about the Spanish galleon. Some local tours discuss the Dòideag and the treasure legends.

Conclusion

The legends of Mull are more than echoes. They are stitched into the island itself. These stories persist not because they are written, but because they are remembered. They travel in voice and place, in the mist off the sea and the stillness of ruined stone. To know Mull’s folklore is to see more than landscape. It is to recognise the island as a living archive of experience and belief. Whether you believe the tales or not, the island does not care. It will continue to whisper them, long after footfalls fade and names are forgotten.

Read the full Water Horse legend from Loch Assapol, as told by Flora Ritchie of Ardtun

Step into a world where ancient legends breathe and history whispers from every stone. This enchanting book invites you on a captivating journey through the heart of Scotland's Inner Hebrides, a land steeped in magic and timeless tales.