Two distinct eras often define the Isle of Mull and its sacred neighbor Iona in the popular imagination. First, there is the ancient geological time of basalt columns and volcanic ruggedness. Then, there is the medieval period of saints, clans, and castles.

However, sandwiched between the Neolithic standing stones and the arrival of St Columba lies a vibrant and turbulent chapter of history. This is the Iron Age.

This era spanned roughly from 600 BC to AD 400. It was a time when the landscape of the Inner Hebrides bristled with fortifications. Petty kings and skilled metalworkers defined this era. Farmers coaxed life from the damp peaty soil while keeping one eye on the horizon for raiders. To walk the hills of Mull today is to walk through the ruins of this lost society. You just have to know where to look.

The Landscape of Defense

If you look closely at the Ordnance Survey maps of Mull you will see the word Dun repeated over and over again. Dun is pronounced doon. It is the Gaelic word for a fort or castle. In the context of the Iron Age, it usually refers to a small fortified settlement.

Mull is not an island of vast sprawling hillforts like those found in the Scottish Borders. Instead, decentralized power defined the Iron Age here.

The geography of Mull dictated the nature of its defense. The jagged coastline and precipitous cliffs combined with hidden glens to shape how people lived. The communities here did not build massive cities. They built strongholds for extended families or small clans.

Promontory Forts

Builders often sited these structures on promontory forts. These are fingers of rock jutting out into the sea. Steep cliffs provided natural defense on three sides. The builders only needed a single heavy wall to close off the landward approach.

Sloc a’ Mhuilt on the Ross of Mull is a prime instance of this strategy. It is a place where the roar of the Atlantic would have been the constant soundtrack to daily life. These were not just military bunkers. They were homes and symbols of status. They were visible claims to the land.

The Atlantic Roundhouses

The most iconic structure of the Scottish Iron Age is the broch. This is a hollow walled drystone tower found primarily in the north and west of Scotland.

There is a long standing archaeological debate about whether Mull has true brochs or simply very complex duns. The distinction feels academic for the visitor standing in the shadow of Dun nan Gall.

The Fort of the Foreigners

Located on the north west coast near Ballygown, Dun nan Gall translates to The Fort of the Foreigners. It is one of the most impressive prehistoric sites on the island. It sits on a rocky knoll. Its drystone walls still stand several meters high in places.

Unlike the simple duns, Dun nan Gall features the architectural complexity associated with brochs. It has thick walls that likely contained galleries. These were spaces within the walls themselves. It also features a guard cell protecting the entrance.

The name itself is intriguing. It may date from a later period. It perhaps refers to Vikings or Norse Gaels. Yet the stones themselves speak of an earlier time.

The Sentinel of Loch Tuath

Further south near Burg, overlooking the waters of Loch Tuath, lies another contender for the title of Mull’s best-preserved fortification: Dun Aisgain.

Like Dun nan Gall, Dun Aisgain blurs the line between dun and broch. It sits atop a rocky knoll with double-skinned walls that still stand over two meters high. What makes this site particularly evocative is the detail that remains. You can still see the ‘checks’ in the entrance passage, the masonry grooves where a heavy wooden door would have been secured against intruders. Standing here, looking out towards the Treshnish Isles, it is easy to feel the vigilance that defined the Iron Age.

A Symbol of Power

Building such a structure required immense resources and labor. It implies a society with a surplus of food to feed the builders. It suggests a hierarchy strong enough to command them.

Imagine standing inside the central courtyard of Dun nan Gall or Dun Aisgain today. You can picture the timber roundhouse that would have stood within. You can imagine the smell of woodsmoke and the noise of cattle being herded into the enclosure for safety at night.

Islands Within Islands

While duns and brochs guarded the coast and the high ground, a different kind of settlement dominated the lochs. These were the crannogs.

Crannogs are artificial islands built out in the water. Mull has several fine examples. They are often difficult to spot without a trained eye. They appear today as small stony islets overgrown with vegetation.

Engineering Marvels

A crannog was a feat of prehistoric engineering. The builders would drive timber piles into the loch bed. Then, they would heap stones and brushwood inside the ring to create a solid platform.

On top of this foundation they built a roundhouse. Builders often connected it to the shore by a stone or timber causeway. This bridge could be easily defended or dismantled in times of trouble.

Discoveries at Loch Ba

Loch Ba, Loch Sguabain and Lochnameal contain examples of these sites. The crannog offered ultimate protection against wolves and surprise raids. But it also offered something else. It provided freedom from the damp soil.

In the boggy terrain of the Hebrides, a dry timber platform on the water provided a hygienic and secure living space.

Recent underwater archaeology in Scotland reveals that crannogs were often high status sites. Archaeologists uncovered imported pottery and fine metalwork within them. These finds suggest that the Iron Age elite on Mull were comfortable on the water. The inhabitants likely used log boats to navigate the interior lochs as easily as they walked the glens.

Iona Before the Saint

We often associate Iona with St Columba arriving in AD 563 to found his monastery. However, he did not land on a deserted rock. He arrived on an island that had been farmed and defended for centuries. The most significant evidence of this pre Christian past is the hillfort at Dun Cul Bhuirg.

The Western Fort

Dun Cul Bhuirg sits on the western side of Iona. It is far away from the sheltered eastern bay where the Abbey stands. Instead, it is a rugged hillfort occupying a rocky crag.

Excavations here in the middle of the twentieth century proved pivotal for our understanding of the Hebridean Iron Age. Archaeologists uncovered pottery shards dating from between 100 BC and AD 300. This proves that a thriving community lived here long before the monks brought their books and bells.

Watching the Atlantic

The location is telling. The west coast of Iona faces the open Atlantic. A fort here watches over the ocean routes. It perhaps signaled to ships passing between Ireland and the Hebrides.

The people of Dun Cul Bhuirg would have been the ancestors of those who eventually greeted Columba. They were part of a maritime culture. They were deeply connected to the sea for food and trade. The presence of glass beads and specific pottery styles links them to a wider network of Iron Age culture spanning the Irish Sea province.

Life Behind the Walls

What was life actually like for the Iron Age islanders of Mull and Iona? It is easy to focus on the stone walls and assume a life of constant warfare. However, the archaeological record tells a story of domesticity and craft.

The climate would have been slightly better than it is today. Nevertheless, it was still wet. The economy was pastoral and driven by cattle and sheep.

Cattle and Wealth

Cattle were not just food. They were currency. A clan measured its wealth on the hoof. The primary purpose of duns and forts may have been largely economic. They were about protecting this mobile wealth from cattle raiders rather than just defending human lives.

The Skill of the Smiths

Archaeologists also found evidence of industry. Excavations at Torloisk on Mull revealed a fascinating glimpse into Iron Age aesthetics. Researchers found a blue glass dumbbell bead.

Excavators found this small artifact in association with a furnace. It suggests that skilled artisans were either working glass on the island or trading for high prestige items from the continent.

Iron smelting would have been a crucial and almost magical skill. Smiths turned the bog iron found in the peats into swords, axes, and farming tools.

Art in the Home

Pottery was also abundant. The Hebridean ware found at Dun Cul Bhuirg and other sites is distinctively decorated. It features incised patterns and applied cordons.

These vessels were used for cooking and storage. Their decoration implies a culture that took pride in the appearance of even utilitarian objects.

Ritual and Belief

We know less about the spiritual life of the Iron Age inhabitants than we do about their homes. Unlike the Neolithic peoples who left us stone circles like Lochbuie, the Iron Age people of Mull did not build vast ritual monuments.

Sacred Landscapes

Their beliefs are likely buried in the landscape itself. They may have cast votive offerings into lochs which was a common practice in the Celtic world. Other beliefs likely centered on the domestic rituals of the hearth.

However, the transition from the Iron Age to the Early Historic period gives us clues. The fact that Columba chose Iona might not be a coincidence. It was a place with an existing high status settlement.

Early Christian sites often superimposed themselves on places of existing power or spiritual significance. The fairy mounds of later folklore often inhabit the physical remains of Iron Age duns. This suggests a lingering cultural memory that these places were significant. They were perhaps viewed as gateways to the Otherworld.

The Transition to History

The Iron Age on Mull did not end with a bang. It slowly morphed into the Early Historic period. By the fifth and sixth centuries AD the people of Mull were part of the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata.

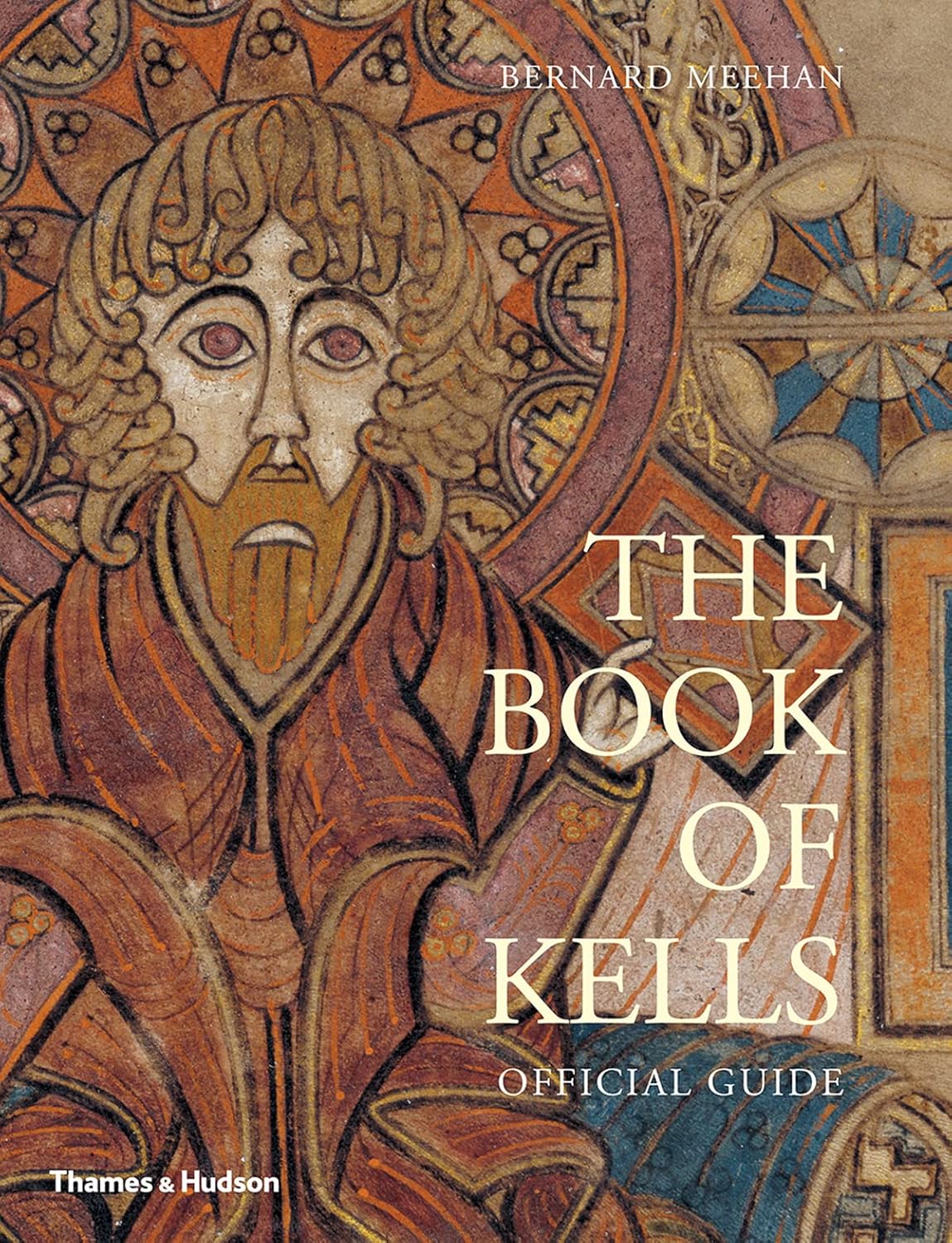

The fortifications at places like Dun nan Gall likely remained in use or were reoccupied. The skills in metalworking and stone carving developed during the Iron Age laid the foundation for the artistic explosion of the monastic period. This culminated in masterpieces like the Book of Kells.

The Book of Kells, dating from about 800, is a brilliantly decorated manuscript of the four Gospels. This new official guide, by the former Keeper of Manuscripts at Trinity College Library, Dublin, provides fascinating insights into the Book of Kells, revealing the astounding detail and richness of one of the greatest works of medieval art.

Watch this video on the Lephin excavation to see how archaeologists are uncovering the Norse and Medieval history that followed the Iron Age on Mull.

A Lasting Legacy

The Dun evolved into the castle. The tribal chief evolved into the King of Scots. Yet the footprint of the Iron Age remains.

Tumbled stones on the headlands mark this legacy. Dark loch waters hide the faint outline of crannogs. The very name of Iona itself reminds us that the island was a fortress long before it was a sanctuary.

To understand Mull and Iona today one must look past the Abbey. You must look past the colorful houses of Tobermory. You must look to the grey stones of the duns. They are the silent witnesses to a millennium of survival.